You know, I've long been amazed at the very notion of the "ten-cent plague" -- how so many people got so irrational over comic book and would hold huge bonfires of them regardless of content, how people accepted Wertham's laughably unscientific arguments as gospel, how so much hysteria erupted over Superman and Captain America.

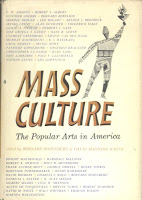

You know, I've long been amazed at the very notion of the "ten-cent plague" -- how so many people got so irrational over comic book and would hold huge bonfires of them regardless of content, how people accepted Wertham's laughably unscientific arguments as gospel, how so much hysteria erupted over Superman and Captain America.I just read a 1957 (I think) essay in Mass Culture: The Popular Arts in America in which one Robert Warshow wrote relayed his thoughts on the "problem" of comic books. What was absolutely fascinating to me was that, despite the fact that he didn't generally like comic books and wished his son didn't read them, he couldn't find a rational or logical argument to support his feelings. He even met (briefly) Bill Gaines and Johnny Craig at the EC offices only a few weeks before Gaines' infamous Senate hearing testimony, and they seemed like normal guys.

I found it an absolutely enlightening and insightful essay on what must have been going through the heads of so many parents at the time, so I'm reproducing the entire article below. (The text was OCR'd from scans of the book. I did a quick proofreading of it, but I apologize for any errors I may have missed.)

Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham

By Robert Warshow

My SON, PAUL, who is eleven years old, belongs to the E.C. Fan-Addict Club, a synthetic organization set up as a promotional device by the Entertaining Comics Group, publishers of Mad ("Tales Calculated to Drive You MAD-Humor in a Jugular Vein"), Panic ("This is No Comic Book, This is a PANIC-Humor in a Varicose Vein"), Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Weird Science-Fantasy, Shock SuspenStories, Crime SuspenStories ("Jolting Tales of Tension in the E.C. Tradition"), and, I imagine, various other such periodicals. For his twenty-five-cent membership fee (soon to be raised to fifty cents), the E.C. Fan-Addict receives a humorously phrased certificate of membership, a wallet-size "identification card," a pin and a shoulder-patch bearing the club emblem, and occasional mailings of the club bulletin, which publishes chitchat about the writers, artists, and editors, releases trial balloons on ideas for new comic books, lists members' requests for back numbers, and in general tries to foster in the membership a sense of identification with this particular publishing company and its staff. B.C. Fan-Addict Club Bulletin Number 2, March 1954, also suggests some practical activities for the members. "Everytime you pass your newsstand, fish out the E.C.'s from the bottom of the piles or racks and put 'em on top… BUT PLEASE, YOU MONSTERS, DO IT NEATLY!"

Paul, I think, does not quite take this "club" with full seriousness, but it is clear that he does in some way value his membership in it, at least for the present. He has had the club shoulder-patch put on one of his jackets, and when his membership pin broke recently he took the trouble to send for a new one. He has recruited a few of his schoolmates into the organization. If left free to do so, he will buy any comic book which bears the E.C. trademark, and is usually quite satisfied with the purchase. This is not a matter of "loyalty," but seems to reflect some real standard of discrimination; he has occasionally sampled other comic books which imitate the E.C. group and finds them inferior.

It should be said that the E.C. comics do in fact display a certain imaginative flair. Mad and Panic are devoted to a wild, undisciplined machine-gun attack on American popular culture, creating an atmosphere of nagging hilarity something like the clowning of Jerry Lewis. They have come out with covers parodying the Saturday Evening Post and Life, and once with a vaguely "serious" cover in imitation of magazines like Harper's or the Atlantic. (“Do you want to look like an idiot reading comic books all your life? Buy Mad, then you can look like an idiot reading high-class literature.") The current issue of Mad (dated August) has Leonardo's Mona Lisa on the cover, smiling as enigmatically as. ever and cradling a copy of Mad in her arms. The tendency of the humor, in its insistent violence, is to reduce all culture to indiscriminate anarchy. These comic books are in a line of descent from the Marx Brothers, from the Three Stooges whose funniest business is to poke their fingers in each other's eyes, and from that comic orchestra which starts out playing “serious" music and ends up with all the instruments smashed. A very funny parody of the comic strip "Little Orphan Annie," in Mad or Panic, shows Annie cut into small pieces by a train because Daddy Warbucks' watch is slow and he has arrived just too late for the last minute; Annie's detached head complains: "It hurts when I laugh." The parody ends with the most obvious and most vulgar explanation of why Annie calls Daddy Warbucks "Daddy"; 1 had some difficulty in explaining that joke to Paul. One of the funnier stories in Panic tells of a man who finds himself on the television program “This Is Your Life"; as his old friends and neighbors appear one by one to fill in the story of his life, it becomes clear that nobody has seen his wife since II :30 P.M. on the ninth of October 1943; shortly before that he had made some rather significant purchases: arsenic, a shovel, quicklime. Evidence piles up, including the actual bones of his wife (dug up by his old dog, Rover, who also appears on the program and will do nothing but growl at his former master). At the end of the. program, of course, the man is arrested for murder; television's assault on privacy has reached its logical conclusion. I understand that Mad is rather popular among college students, and I have myself read it with a kind of irritated pleasure.

The straightforward crime and horror comics, such as Shock SuspenStories, Crime SuspenStories, or The Vault of Horror, exhibit the same undisciplined imaginativeness and valence without the leavening of humor. One of the more gruesome stories in Crime SuspenStories is simply a "serious" version of the story I have outlined from Panic: again a man murders his wife (this time with an ax) and buries her in the back yard, and again he is trapped on a television program. In another story, a girl some ten or eleven years old, unhappy in her home life, shoots her father, frames her mother and the mother's lover for the murder, and after their death in the electric chair (“Mommy went first. Then Steve.") is shown living happily with Aunt Kate, who can give her the emotional security she has lacked. The child winks at us from the last panel in appreciation of her own cleverness. Some of the stories, if one takes them simply in terms of their plots, are not unlike the stories of Poe or other writers of horror tales; the publishers of such comic books have not failed to point this out. But of course the bareness of the comic-book form makes an enormous difference. Both the humor and the horror in their utter lack of modulation yield too readily to the child's desire to receive his satisfactions immediately, thus tending to subvert one of the chief elements in the process of growing up, which is to learn to wait; a child's developing appreciation of the complexity of good literature is surely one of the things that contribute to his eventual acceptance of the complexity of life.

I do not suppose that Paul's enthusiasm for the products of this particular publisher will necessarily last very long. At various times in the past he has been a devotee of the Dell Publishing Company (Gene Autry, Red Ryder, Tarzan, The Lone Ranger, etc.), National Comics (Superman, Action Comics, Batman, etc.), Captain Marvel, The Marvel Family, Zoo Funnies (very briefly), Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, and, on a higher level, Pogo Possum. He has around a hundred and fifty comic books in his room, though he plans to weed out some of those which no longer interest him. He keeps closely aware of dates· of publication and watches the newsstands from day to day and from corner to corner if possible; when a comic book he is concerned with is late in appearing, 11e is likely to get in touch with the publisher to find out what has caused the delay. During the Pogo period, indeed, he seemed to be in almost constant communication with Walt Kelly and the Post-HaIl Syndicate, asking for original drawings (he has two of them), investigating delays in publication of the comic books (there are quarterly 1S-cent comic books, published by Dell, in addition to the daily newspaper strip and the frequent paperbound volumes published at one dollar by Simon and Schuster), or tracking down rumors that a Pogo shirt or some other object was to be put on the market (the rumors were false; Pogo is being kept free of "commercialization"). During the 1952 presidential campaign, Pogo was put forward as a "candidate," and there were buttons saying "I Go Pogo"; Paul managed to acquire about a dozen of these, although, as he was told, they were intended primarily for distribution among college students. Even now he maintains a distant fondness for Pogo, but I am no longer required to buy the New York Post every day in order to save the daily strips for him. I think that Paul's desire to put himself directly in touch with the processes by which the comic books are produced may be the expression of a fundamental detachment which helps to protect him from them; the comic books are not a "universe~' to him, but simply objects produced for his entertainment.

When Paul was home from school for his spring vacation this year, I took him and two of his classmates to visit the offices of the Entertaining Comics Group at 225 Lafayette Street. (I had been unable to find the company in the telephone book until 1 thought of looking it up as "Educational Comics"; I am told that this is one of five corporate names under which the firm operates.) As it turned out, there was nothing to be seen except a small anteroom containing a pretty receptionist and a rack of comic books; the editors were in conference and could not be disturbed. (Of course I knew there must be conferences, but this discovery that they actually occur at a particular time and place somehow struck me; I should have liked to know how the editors talked to each other:) In spite of our confinement to the anteroom, however, the children seemed to experience as great a sense of exaltation as if they had found themselves in the actual presence of, say, Gary Cooper.

One of Paul's two friends signed up there and then in the E. C. FanAddict Club (Paul had recruited the other one into the club earlier) and each boy bought seven or eight back numbers. When the receptionist obligingly went into the inner offices to see if she could collect a few autographs, the boys by crowding· around the door as she opened it managed to catch a glimpse of one of the artists, Johnny Craig, whom Paul recognized from a drawing of him that bad appeared in one of the comic books. In response to the boys' excitement, the door was finally opened wide so that for a few seconds they could look at Mr. Craig; he waved at them pleasantly from behind his drawing board and then the door was closed. Before we left, the publisher himself, William Gaines, passed through the anteroom, presumably on his way to the men's room. He too was recognized, shook hands with the boys, and gave them his autograph.

I am sure the children's enthusiasm contained some element of self-parody, or at any rate an effort to live up to the situation-after all, a child is often very uncertain about what is exciting, and how much. It is quite likely that the little sheets of paper bearing the precious autographs have all been misplaced by now. But there is no doubt that the excursion was a great success.

A few weeks later Mr. Gaines testified before a Congressional committee that is investigating the effects of comic books on children and their relation to juvenile delinquency. Mr. Gaines, as one would expect, was opposed to any suggestion that comic books be censored. In his opinion, he said, the only restrictions on the. editors· of comic books should be the ordinary restrictions of good taste. Senator Kefauver presented for his examination the cover of an issue of Crime SuspenStories (drawn by Johnny Craig) which shows a man holding by its long blond hair the severed head of a woman. In the man's other hand is the dripping ax with which he has just carried out the decapitation, and the lower part of the woman's body, with the skirt well up on the plump thighs, appears in the background. It was an illustration for the story I have described in which·the murderer is finally trapped on a television program. Did Mr. Gaines think this cover in good taste? Yes, he did-for a horror comic. If the head had been held a little higher, so as to show blood dripping from the severed neck, that would have been bad taste. Mr.· Gaines went on to say that he considers himself to be the originator of horror comics and is proud of it. He mentioned also that he is a graduate of the New York University School of Education, qualified to teach in the high schools.

I did not fail to clip the report of Mr. Gaines's testimony from the Times and send it to Paul, together with a note in which I said that while I was in some confusion about the comic-book question, at least I was sure I did not see what Mr. Gaines had to be so proud about. But Paul has learned a few things in the course of the running argument about comic books that has gone on between us. He thanked me for sending the clipping and declined to be drawn into a discussion. Such discussions have not proved very fruitfnl for him in the past.

They have not been very fruitfnl for me either. I know that I don't like the comics myself and that it makes me uncomfortable to see Paul read~ ing them. But it's hard to· explain to Paul why I feel this· way, and somewhere along the line it seems to have been established that Paul is always entitled to an explanation: he is a child of our time.

I said once· that the gross and continual violence of the comic books was objectionable.

He said: "What's so terrible about things being exciting?"

Well, nothing really; but there are books that are much more exciting, and the comics keep you from reading the books.

But I read books too. (He does, especially when there are no comics available.)

Why read the comics at all?

But you said yourself that Mad is pretty good. You gotta admit!

Yes, I know I did. But it's not that good.... Oh, the comics are just stupid, that's all, and I don't see why you should be wasting so much time with them.

Maybe they're stupid sometimes. But look at this one. This one is really good. Just read it! Why won't you just read it?

Usually I refuse to "just read it," but that puts me at once at a disadvantage. How can I condemn something without knowing what it is? And sometimes, when I do read it, I am forced to grant that maybe this particular story does have a certain minimal distinction, and then I'm lost. Didn't I say myself that Mad is pretty good?

I suppose this kind of discussion can be carried on better than I seem able to do, but it's a bad business getting into discussions anyway. If you're against comic books, then you say: no comic books. I understand there are parents who manage to do that.· The best-or worst-that has happened to Paul was a limit on the number of comic books he was allowed to have in a week: I think it was three. But· that was intolerable; there were special occasions, efforts to borrow against next week, negotiations for revision of the allotment; there was always a discussion.

The fundamental difficulty, in a way-the thing that leaves both Paul and me uncertain of our ground-is that the comics obviously do not constitute a serious problem in his life. He is in that Fan-Addict Club, all right, and he likes to make a big show of being interested in E.C. comics above all else that the world has to offer, but he and I both know that while he may be a fan, he is not an addict. His life at school is pretty busy (this has been his first year at school away from home) and comics are not encouraged, though they certainly do find their way in. Paul subscribes to Mad and, I think, Pogo (also to Zoo Funnies and Atomic Mouse -- but he doesn't read those any more), and he is still inclined to haunt the newsstands when he is in New York; indeed, the first thing he wants to do when he gets off the train is buy a comic. In spite of all obstacles, I suppose he manages to read a hundred in a year, at worst perhaps even a hundred and fifty-that would take maybe seventy-five to a hundred hours. On the other hand, he doesn't see much television or listen much to the radio, and he does read books, draw, paint, play with toads, look at things through a microscope, write stories and poems, imitate Jerry Lewis, and in general do everything that one could reasonably want him to do, plus a few extras like skiing and riding. He seems to me a more alert, skillful, and self-possessed child than I or any of my friends were at eleven, if that's any measure.

Moreover, I can't see that his hundred or hundred and fifty comic books are having any very specific effects on him. The bloodiest of ax murders apparently does not disturb his sleep or increase the violence of his own impulses. Mad and Panic have helped to develop in him a style of humor which may occasionally be· wearing but is in general pretty successful; and anyway, Jerry Lewis has had as much to do with this as the comics. Paul's writing is highly melodramatic, but that's only to be expected, and he is more likely to model himself on Erie Stanley Gardner or Wilkie Coilins than on Crime SuspenStories. Sometimes the melodrama goes over the line into the gruesome, and in that the comic books no doubt play a role; but if there were no comic books, Paul would be reading things like "The Pit and the Pendulum" or The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym-which, to be sure, would be better. Now and then he has expressed a desire to be a comic book artist when he grows up, or a television comedian. So far as I can judge, he has no inclination to accept as real the comic-book conception of human nature which sees everyone as a potential criminal and every criminal as an absolute criminal.

As you see, I really don't have much reason to complain; that's why Paul wins the arguments. But of course I complain anyway. I don't like the comic books -- not even Mad, whatever I may have unguardedly allowed myself to say -- and I would prefer it if Paul did not read them. Like most middle-class parents, I devote a· good deal of over-anxious attention to his education, to the "influences" that play on him and the "problems" that arise for him. Almost anything in his life is likely to seem important to me, and I find it hard to accept the idea that there should be one area of his experience, apparently of considerable importance to him, which will have no important consequences. One comic book a week or ten, they must have an effect. How can I be expected to believe that it will be a good one?

Testifying in opposition to Mr. Gaines at the Congressional hearing was Dr. Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist who has specialized in work with problem and delinquent children. Dr. Wertham has been studying and attacking the comic books for a number of years. His position on the question is now presented in full in his recently published book Seduction of the Innocent.

The most impressive part of the book is its illustrations: two dozen or so examples of comic-book art displaying the outer limits of that "good taste" which Mr. Gaines suggests might be a sufficient restraint upon the editors. There is a picture of a baseball game in which the ball is a man's head with one eye dangling from its socket, the bat is a severed leg, the catcher wears a dismembered human torso as chest protector, the baselines are marked with stretched-out intestines, the bases are marked with the lungs, liver, and heart, the rosin-bag is the dead man's stomach, and the umpire dusts off home plate with the scalp. There is a close-up of a hanged man, tongue protruding, eyeballs turned back, the break in the neck clearly drawn. Another scene shows two men being dragged to death face down over a rocky road. “A couple more miles oughta do th' trick!" says the driver of the car. "It better," says his companion. "These ****!1 GRAVEL ROADS are tough on tires!" "But you gotta admit," replies the driver, "there's nothing like 'em for ERASING FACES!" And so on. Dr. Wertham could surely have presented many more such examples if he had the space and could have obtained permission to reproduce them. From Paul's collection, I recall with special uneasiness a story in which a rotting corpse returns from the grave; in full color, the hues and contours of decay were something to see.

Among the recurrent motifs of the comic books, Dr. Wertham lists: hanging, flagellation, rape, torture of women, tying up of women, injury to the eye (one of the pictures he reproduces shows a horrifying close-up of a woman's eye about to be pierced by an ice-pick). If a child reads ten comics of this sort a week (a not unusual figure), he may absorb in the course of a year from fifteen hundred to two thousand stories emphasizing these themes (a comic book contains three or four stories). If he takes them with any seriousness at all-and it is difficult to believe that he will not-they surely cannot fail to affect his developing attitudes towards violence, sex, and social restraint.

What the effects will be, and how deep-seated, is not so easy to determine. And here Dr. Wertham is not very helpful. When he tells us of children who have been found hanging, with a comic-book nearby opened to a picture of a hanging, one can readily share his alarm. The fact that these children were probably seriously disturbed before they ever read a comic book, and the fact that fantasies of hanging are in any case common among children, does not relieve one of the feeling that comic books may have provided the immediate stimulus that led to these deaths. Even if there were no children who actually hanged themselves, is it conceivable that comic books which play so directly and so graphically on their deepest anxieties should be without evil consequences? On the other hand, when Dr. Wertham tells us of children who have injured themselves trying to fly because they have read Superman or Captain Marvel, one becomes skeptical. Children always want to fly and are always likely to try it. The elimination of Superman will not eliminate this sort of incident. Like many other children, I made my own attempt to fly after seeing Peter Pan; as I recall, I didn't really expect it to work, but I thought: who knows?

In general, Dr. Wertham pursues his argument with a humorless dedication that tends to put all phenomena and all evidence on the same level. Discussing Superman, he suggests that it wouldn't take much to change the "S" on that great chest to "S.S." With a straight face he tells us of a little boy who was asked what he wanted to be when he grew up and said, "1 want to be a sex maniac!" He objects to advertisements for binoculars in comic books because a city child can have nothing to do with binoculars except to spy on the neighbors. He reports the case of a boy of twelve who had misbehaved with his sister and threatened to break her arm if she told anybody. "This is not the kind of thing that boys used to tell their little sisters," Dr. Wertham informs us. He quotes a sociologist who "analyzed" ten comic-book heroes of the Superman type and found that all of them "may well be designated as psychopathic deviates." As an indication that there are some children "who are influenced in the right direction by thoughtful parents," he tells us of the four-year-old son of one of his associates who was in the hospital with scarlet fever; when the nurses offered him some comic books, the worthy child refused them, "explaining . . . that his father had said they are not good for children." Dr. Wertham will take at face value anything a child tells him, either as evidence of the harmful effects of the comic books ("I think sex all boils down to anxiety," one boy told him; where could he have got such an idea except from the comics?) or as direct support for his own views: he quotes approvingly a letter by a thirteen-year-old boy taking solemn exception to the display of nudity in comic books, and a fourteen-year-old boy's analysis of the economic motives which lead psychiatrists to give their endorsements to comic books. I suspect it would be a dull child indeed who could go to Dr. Wertham's clinic and not discover very quickly that most of his problematical behavior can be explained in terms of the comic books.

The publishers complain with justice that Dr. Wertham makes no distinction between bad comic books and "good" ones. The Dell Publishing Company, for instance, the largest of the publishers, claims to have no objectionable comics on its list, which runs to titles like Donald Duck and The Lone Ranger. National Comics Publications (Superman, etc.), which runs second to Dell, likewise claims to avoid objectionable material and has an "editorial code" which specifically forbids the grosser forms of violence or any undue emphasis on sex. (If anything, this "code" is too puritanical, but mechanically fabricated culture can only be held in check by mechanical restrictions.) Dr. Wertham is largely able to ignore the distinction between "bad" and "good" because most of us find it hard to conceive of what a "good" comic book might be.

Yet in terms of their effect on children, there must be a significant difference between The Lone Ranger or Superman or Sergeant Preston of the Yukon on the one hand and, say, the comic book from which Dr. Wertham took that picture of a baseball game played with the disconnected parts of a human body. If The Lone Ranger and Superman are bad, they are bad in a different way and on a different level. They are crude, unimaginative, banal, vulgar, ultimately corrupting. They are also, as Dr. Wertham claims, violent-but always within certain limits. Perhaps the worst thing they do is to meet the juvenile imagination on its crudest level and offer it an immediate and stereotyped satisfaction. That may be bad enough, but very much the same things could be said of much of our radio and television entertainment and many of our mass-circulation magazines. The objection to the more unrestrained horror and crime comics must be a different one. It is even possible that these outrageous productions may be in one sense "better" than The Lone Ranger or Sergeant Preston, for in their absolute lack of restraint they tend to be somewhat livelier and more imaginative; certainly they are often less boring. But that does not make them any less objectionable as reading matter for children. Quite the contrary, in fact: Superman and Donald Duck and The Lone Ranger are stultifying; Crime SuspenStories and The Vault of Horror are stimulating.

A few years ago I heard Dr. Wertham debate with Al Capp on the radio. Mr. Capp at that time had introduced into Li'! Abner the story of the shmoos, agreeable little animals of 100 per cent utility who would fall down dead in an ecstasy of joy if one merely looked at them hungrily. All the parts of a shmoo's body, except the eyes, were edible, tasting variously like porterhouse steak, butter, turkey, probably even chocolate cake; and the eyes were useful as suspender buttons. Mr. Capp's fantasy was in this -as, 1 think, in most of his work-mechanical and rather tasteless. But Dr. Wertham was not content to say anything like that. For him, the story of the shmoos was an incitement to sadistic violence comparable to anything else he had discovered in his reading of comics. He was especially disturbed by the use of the shmoo's eyes as suspender buttons, something he took to be merely another repetition of that motif of injury to the eye which is exemplified in his present book by the picture of a woman about to be blinded with an ice-pick. In the violence of Dr. Wertham's discourse on this subject one got a glimpse of his limitations as an investigator of social phenomena.

For the fact is that Dr. Wertham's picture of society and human nature is one that a reader of comic books-at any rate, let us say, a reader of the "good" comic books-might not find entirely unfamiliar. Dr. Wertham's world, like the world of the comic books, is one where the logic of personal interest is inexorable, and Seduction of the Innocent is a kind of crime comic book for parents, as its lurid title alone would lead one to expect. There is the same simple conception of motives, the same sense of overhanging doom, the same melodramatic emphasis on pathology, the same direct and immediate relation between cause and effect. If a juvenile criminal is found in possession of comic books, the comic books produced the crime. If a publisher of comic books, alarmed by attacks on the industry, retains a psychiatrist to advise him on suitable content for his publications, it f6110ws necessarily that the arrangement is a dishonest one. If a psychiatrist accepts a fee of perhaps $150 a month for carrying out such an assignment (to judge by what Dr. Wertham himself tells us, the fees are not particularly high), that psychiatrist has been "bought"; it is of no consequence to point out how easily a psychiatrist can make $150. It is therefore all right to appeal to the authority of a sociologist who has "analyzed" Superman "according to criteria worked out by the psychologist Gordon W. Allport" and has found him to be a "psychopathic deviate," but no authority whatever can be attached to the "bought" psychiatrist who has been professionally engaged in the problem of comic books. If no comic-book publisher has been prosecuted under the laws against contributing to the delinquency of minors, it cannot be because those laws may not be applicable; it must be because "no district attorney, no judge, no complainant, has ever had the courage to make a complaint."

Dr. Wertham also exhibits a moral confusion which, even if it does not correspond exactly to anything in the comic books, one can still hope will not gain a footing among children. Comic-book writers and artists working for the more irresponsible publishers have told Dr. Wertham of receiving instructions to put more violence, more blood, and more sex into their work, and of how reluctantly they have carried out these instructions. Dr. Wertham writes: "Crime-comic-book writers should not be blamed for comic books. They are not free men. They are told what to do and they do it or else. They often are, I have found, very critical of comics.... But of course ... they have to be afraid of the ruthless economic power of the comic-book industry. In every letter I have received from a writer, stress is laid on requests to keep his identity secret." What can Dr. Wertham mean by that ominous "or else" which explains everything and pardons everything? Will the recalcitrant writer be dragged face down over a rocky road? Surely not. What Dr. Wertham means is simply that the man might lose his job and be forced to find less lucrative employment. This economic motive is a sufficient excuse for the man who thought up that gruesome baseball game-I suppose because he is a "worker." But it is no excuse for a psychiatrist who advises the publishers of Superman and sees to it that no dismembered bodies are played with in that comic book. And of course it is no excuse for a publisher-he is "the industry." This monolithic concept of "the industry" is what makes it pointless to discover whether there is any difference between one publisher and another; it was not men who produced that baseball game-it was "the industry." Would Dr. Wertham suggest to the children who come to his clinic that they cannot be held responsible for anything they do - so long as they are doing it to make a living? I am sure he would not. But he does quote with the greatest respect the words of that intelligent fourteen-year-old who was able to see so clearly that if a psychiatrist receives a fee, one can obviously not expect that he will continue to act honestly. And it is not too hard to surmise where this young student of society got the idea.

Apparently, also, when you are fighting a "ruthless industry" you are under no obligation to be invariably careful about what you say. Dr. Wertham very properly makes fun of the psychiatric defenders of comic books who consider it a sufficient justification of anything to say that it satisfies a "deep" need of a child. But on his side of the argument he is willing to put forward some equally questionable "deep" analysis of his own, most notably in his discussion of the supposedly equivocal relation between Batman and the young boy Robin; this particular analysis seems to me a piece of utter frivolity. He is also willing to create the impression that all comic books are on the level of the worst of them, and that psychiatrists have endorsed even such horrors as the piercing of women's eyes and the whimsical dismemberment of bodies. (In fact, the function performed by the reputable psychiatrists who have acted as advisers to the publishers has been to suggest what kind of comic books would be "healthy" reading for children. One can disagree with their idea of what is "healthy," as Dr. Wertham does, or one can be troubled, as I am, at the addition of this new element of fabrication to cultural objects already so mechanical; but there is no justification for implying that these psychiatrists have been acting dishonestly or irresponsibly.)

None of this, however, can entirely destroy Dr. Wertham's case. It remains true that there is something questionable in the tendency of psychiatrists to place such stress on the supposed. psychological needs of children as to encourage the spread of material which is at best subversive of the same children's literacy, sensitivity, and general cultivation. Superman and The Three Musketeers may serve the same psychological needs, but it still matters whether a child reads one or the other. We are left also with the underworld of publishing which produced that baseball game, which I don't suppose I shall easily forget, and with Mr. Gaines' notions of good taste, with the children who have hanged themselves, and with the advertisements for switch-blade knives, pellet guns, and breast developers which accompany the sadistic and erotic stimulations of the worst comic books. We are left above all with the fact that for many thousands of children comic books, whether "bad" or-"good," represent virtually their only contact with culture. There are children in the schools of our large cities who carry knives and sometimes guns. There are children who reach the last year of high school without ever reading a single book. Even leaving aside the increase in juvenile crime, there seem to be larger numbers of children than ever before who, without going over the line into criminality, live almost entirely in a juvenile underground largely out of touch with the demands of social responsibility, culture, and personal refinement, and who grow up into an unhappy isolation where they are sustained by little else but the routine of the working day, the unceasing clamor of television and the juke boxes, and still, in their adult years, the comic books. This is a very fundamental problem; to blame the comic books, as Dr. Wertham does, is simple-minded. But to say that the comics do not contribute· to the situation would be like denying the importance of the children's classics and the great English and European novels in the development of an educated man.

The problem of regulation or even suppression of the comic books, however, is a great deal more difficult than Dr. Wertham imagines. If the publication of comic books were forbidden, surely something on an equally low level would appear to take their place. Children do need some· "sinful" world of their own to which they can retreat from the demands of the adult world; as we sweep away one juvenile dung heap, they will move on to another. The point is to see that the dung heap does not swallow them up, and to hope it· may be one that will bring forth blossoms. But our power is limited; it is the children who have the initiative: they will choose what they want. In any case, it is not likely that the level of literacy and culture would be significantly raised if the children simply turned their attention more exclusively to television and the love, crime, and movie magazines. Dr. Wertham, to be sure, seems quite ready to carry his fight into these areas as well; ultimately, one suspects, he would like to see our culture entirely hygienic. I cannot agree with this tendency. I myself would not like to live surrounded by the kind of culture Dr. Wertham could thoroughly approve of, and what I would not like for myself I would hardly desire for Paul. The children must take their chances like the rest of us. But when Dr. Wertham is dealing with the worst of the comic books he is on strong ground; some kind of regulation seems necessary-indeed,. the more respectable publishers of comic books might reasonably welcome it-and I think one must accept Dr. Wertham's contention that no real problem of "freedom of expression" is involved, except that it may be difficult to frame a law that would not open the way to a wider censorship.

All this has taken me a long way from Paul, who doesn't carry a switchblade knife and has so far been dissuaded even from subscribing to Charles Atlas' body-building course. Paul only clutches at his chest now and then, says something like "arrgh," and drops dead; and he no longer does that very often. Perhaps even Dr. Wertham would not be greatly alarmed about Paul. But I would not say that Paul is not involved in the problem at all. Even if he "needs" Superman, I would prefer that he didn't read it. And what he does read is not even Superman, which is too juvenile for him; he reads some of the liveliest, bloodiest, and worst material that the "ruthless" comic-book industry has to offer-he is an E.C. Fan-Addict.

I think my position is that I would be happy if Senator Kefauver and Dr. Wertham could find some way to make it impossible for Paul to get any comic books. But I'd rather Paul didn't get the idea that I had anything to do with it.

1 comments:

It's funny how pervasive the anti-comic-book mentality was at the time.

You can see it in some old Peanuts strips.

Up until recently I had a novel, written in the early '60s I think, aimed at about a ten-year-old level, in which a brother and sister find that their little brother had concealed a horror comic in his room. They concluded he must have found it somewhere, because he knew better than to buy any such evil thing. Just to be on the safe side, they burned it before their parents could find out about it. Note: this isn't what the book was *about*; it was about a witch who lived next door or something. It was just a little incident in the first chapter.

And in Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy, there's a part where the matriarch of this huge clan/starship-crew talks about how every so often she has to arrange to have the young men's bunks searched for contraband like comic books. This, in a book that's supposed to be set far in the future.

Post a Comment