This comes from an actual email discussion I had at work. A co-worker asked, "What's up with superheroes always standing on top of buildings... a lot of crime up there?" I made a joke about the view being really cool, in part because you didn't have to look through some ugly railing they put up to prevent twits from jumping off the side to their deaths. That prompted his observation that super-folk are always leaping over the edge whether or not they can actually fly.

Which brings me to how I've actually been defining what it means to be a superhero. Namely, that a superhero is someone who can confidently leap off the side of a tall building confident that they won't get hurt. Flight is the obvious (well, obvious in the context of comic books) solution.

"Ah, but what about Batman? Or Daredevil? They can't fly."

No, but those types of characters are both A) athletic and B) resourceful enough that they have other options to prevent them from hitting the ground with a splat. Often involving ropes and cables.

Although, it sometimes just involves being really, really acrobatic.

Another possibility, too, is that the character is just so tough that smashing on the ground is just going to put a dent in the pavement, without actually doing them any harm.

The point is that a superhero can casually leap off a building with no real concerns about becoming a puddle on the street. That's how you can lump Superman (an alien) in with the likes of Thor (a god) and Iron Man (a regular guy with lots of technology) and the Vision (an android) and Zatara (a magician) and the Phantom (just a really athletic guy) and Deadman (a ghost) and Plastic Man (an altered human).

Of course, the down side to my definition is that it also includes characters most people wouldn't normally think of as super-powered. Like Wile E. Coyote.

On this day, pretty much every year, somebody trots out the cover to Street & Smith's 1942 comic Remember Pearl Harbor to help commemorate the day in 1941 when Pearl Harbor was bombed. Sometimes, it's accompanied by some basic information, like that it was drawn by Jack Binder and was released in early 1942 as the first comic book to acknowledge the bombing in any capacity. By all accounts I've read (not having been able to read the actual comic myself) the story not surprisingly portrays the Japanese in a relatively poor light, and pretty blatantly plays into American nationalism.

On this day, pretty much every year, somebody trots out the cover to Street & Smith's 1942 comic Remember Pearl Harbor to help commemorate the day in 1941 when Pearl Harbor was bombed. Sometimes, it's accompanied by some basic information, like that it was drawn by Jack Binder and was released in early 1942 as the first comic book to acknowledge the bombing in any capacity. By all accounts I've read (not having been able to read the actual comic myself) the story not surprisingly portrays the Japanese in a relatively poor light, and pretty blatantly plays into American nationalism.

Here's the one piece of interior art I've been able to find online, and the American iconography is obvious to the point of being over-the-top...

Even the most subtle imagery -- the huge mortar cannon coming out of Uncle Sam's crotch -- is barely less than glaring. It's difficult to argue that the book is NOT jingoistic.

If you've read any comics from the early 1940s, you've almsot undoubtably stumbled across similar expressions of nationalism. Whether it was obvious caricatures of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin; or yellow-faced, buck-toothed Japanese villains; or Superman filming the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima. It was beyond just American pride, it was almost a reveling in utterly defeating the bad guys. It wasn't sufficient to overpower their military, but there was a sense that they needed to be humiliated and ground into the dirt.

It's unclear to me if that's how U.S. citizens, by and large, actually felt. I know, in my readings about the infamous Keafauver Hearings and associated boycotts of the comic industry, that, while there were indeed people acting on the far side of irrationality and organizing comic book bonfires and the like, that wasn't exactly the norm either and a number of people in fact maintained a fair degree of rational behavior despite their concerns as parents. That leads me to wonder just how much the media outlets of the 1940s were distorting American's view -- both with regards to portraying an outrage that might be misdirected or exaggerated, as well as how that portrayal then impacting others' thinking.

There're obvious parallels to today. Characters like Glenn Beck are showing an upset and anger that isn't actually representative of the American public. But by claiming that he is completely typical in that regard has suggested to others that it's perfectly acceptable to amp up their own negative emotions and direct them inappropriately.

Now, admittedly, Hitler exterminating tens of thousands of people in concentration camps is outrageous even compared to 9/11 so more outrage there is understandable. But was it really so deeply visceral and unfocused? Where everything that was remotely unAmerican was considered better off destroyed? Or is that just how it got translated in comic books and movies of the time? I'm asking that sincerely; I don't know.

It's almost every day that I see some news item that makes me shake my head in disgust about how people never learn, and we're almost destined to annihilate our planet in hubris-filled myopia. But every now and then, I come across some anti-intellectual pop culture pap made decades ago that actually makes today's issue seem not quite so bad.

A lot of the news (or, should I say, "news") shows the past few years have highlighted people's differing political ideologies, and how the level of discourse tends to devolve into something that might be heard during a ten-year-old's recess.

"Tax cuts for everyone!"

"Tax cuts for just the middle class!"

"Health care should be affordable for everyone!"

"Don't socialize medicine!"

Obviously, this really does nothing to advance real discourse or dialogue; it's just people shouting over each other. But it makes for an eye-catching public spectacle and the opiate-laced public often gravitates to whoever shouts loudest. The problem with this -- aside from showcasing what a big country of idiots the U.S. is -- is that it doesn't get to the root of the issue. It doesn't get to the core beliefs that really drive people to hold certain opinions. I'm talking about more fundamental beliefs that religion here. I'm talking about "are people basically good or basically evil" types of questions. (For the record, I tend to fall in the "people are basically selfish bastards" camp.)

It turns out that not addressing those root beliefs is why I've never liked (or even understood) the appeal of zombies. On Friday, though, Chuck Klosterman had this piece in the The New York Times explaining the concept in a way that finally gets to, I think, the core belief (or at least a core belief) required to appreciate zombie stories. Klosterman likens the process of destroying zombies (blast one in the head, reload, repeat) to the process of life itself...Every zombie war is a war of attrition. It’s always a numbers game. And it’s more repetitive than complex. In other words, zombie killing is philosophically similar to reading and deleting 400 work e-mails on a Monday morning or filling out paperwork that only generates more paperwork, or following Twitter gossip out of obligation, or performing tedious tasks in which the only true risk is being consumed by the avalanche. The principle downside to any zombie attack is that the zombies will never stop coming; the principle downside to life is that you will be never be finished with whatever it is you do.

Now, granted, many emails that land in my inboxes are drivel that get deleted and some of the work I do can get repetitive, but to hold a basic philosophy of "life = drudgery" like that? That sounds absolutely miserable! I put somewhere between a quarter and a third of my life towards work (with another quarter/third towards sleeping); I refuse to spend that portion of my life being miserable. If I'm going to spend that much of my life on something, I damn well better enjoy it! I noted back in May that I try to make every day better than the one before, and part of that philosophy entails ensuring that I'm generally doing something that I look forward to. Even on those terrible Monday mornings where I'm not really awake, and need several Mt. Dews before my brain starts to process that yes, I have indeed gotten out of bed and gone into the office.

Now, granted, many emails that land in my inboxes are drivel that get deleted and some of the work I do can get repetitive, but to hold a basic philosophy of "life = drudgery" like that? That sounds absolutely miserable! I put somewhere between a quarter and a third of my life towards work (with another quarter/third towards sleeping); I refuse to spend that portion of my life being miserable. If I'm going to spend that much of my life on something, I damn well better enjoy it! I noted back in May that I try to make every day better than the one before, and part of that philosophy entails ensuring that I'm generally doing something that I look forward to. Even on those terrible Monday mornings where I'm not really awake, and need several Mt. Dews before my brain starts to process that yes, I have indeed gotten out of bed and gone into the office.

I understand where Klosterman is coming from here. That's kind of the point of the opening sequence from Shaun of the Dead, isn't it? Isn't that why so many people go through their day at the office, only to come home and vegetate in front of the television until it's time to go to bed? You know, I've seen similar analogies comparing couch potatoes to zombies, but it wasn't until I read Klosterman's piece that I began to really understand how deeply ingrained that mindset is. Zombies are like the Internet and the media and every conversation we don’t want to have. All of it comes at us endlessly (and thoughtlessly), and — if we surrender — we will be overtaken and absorbed. Yet this war is manageable, if not necessarily winnable. As long we keep deleting whatever’s directly in front of us, we survive. We live to eliminate the zombies of tomorrow. We are able to remain human, at least for the time being. Our enemy is relentless and colossal, but also uncreative and stupid.

This is why I don't get the zombie concept. That "endless" stream of media that Klosterman likens to zombies? Where people consider it a "relentless and colossal" enemy? That constant deletedeletedelete that that starts to sound like machine gun fire? I don't look at it like that. I don't see the zombie horde and pull out a shotgun to start annihilating them; I kick back in a lawn chair and offer them a soda. I thrive on that constant bombardment of information. I love getting new information that can change my worldview or make me consider aspects that I hadn't before.

Change isn't something to be feared. Neither physical change, nor the mental change that sometimes needs to occur when presented with new information. That's not to say change is necessarily good, either! Change is simply change, and should be considered on its own merits (or lack thereof).

How did Shaun of the Dead end? Not with the heroes blowing up every zombie in sight, but taking an entirely different approach that embraced who zombies are and how they're different from the living. If you have the inherent belief that work sucks and then you die, you will spend you day blasting zombie after zombie; and, eventually, you'll lose. But if you take matters into your own hands and embrace whatever it is that you can do/are doing, you might well get the girl of your dreams and still be able to play video games in your shed with one of those zombies.

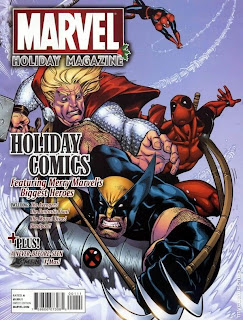

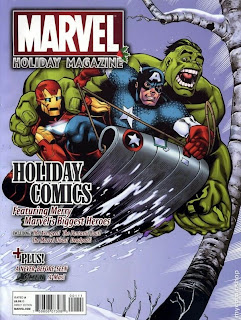

Here are the two covers that were solicited/promoted with this year's Marvel Holiday Magazine...

Here's what I saw in the magazine section of the grocery store today...

As near as I can discern, it's the exact same contents, it's just labeled as a "NEWSSTAND" version.

Personally, I prefer the (uncredited) John Buscema cover, but I'm obviously more of an old-school superhero fan anyway. The art is just repurposed from the old Giant Superhero Holiday Grab-Bag but what I find interesting is that cover has the characters smiling, whereas this year, they're grimacing. Spider-Man's left arm is also at a different angle.

I'm wondering if that was a change made back in 1974 and the artwork paste-ups fell off in the intervening decades, or if that was a contemporary change to reflect the lousy economy? I suspect the former, since there's some obvious clean-up work that could/should have been done on the new version but was not. (There are several residual marks on the page, notably around Thor. Shadows from white paint, perhaps, or part of some paste-up work that was originally done on the Thor figure?)

In any event, I know I certainly would not have given the magazine a second glance with either of those Ryan Stegman covers. (No offense to Stegman, of course, but he's no Buscema!) I'm glad I picked it up because it has some good old-school holiday comic stories, which I'm sure my nephew will appreciate when he gets this from Uncle Sean.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend from out of town stopped by for a visit. It was the first time she'd been to my place, and she looked around a bit before settling down on the couch. She picked up a comic from the coffee table and thumbed through it idly before saying, "So this is where the magic happens? Where you come up with that comic blog every day?"

I brushed it off with something along the lines of my writing hardly being magic, but a minute or two later (after the conversation moved on, of course) I thought of a better answer. What I should have said was, "No, the magic happens up here," and tapped my head a few times. In the first place, it wouldn't have been as dismissive of an answer and in the second place, it's more accurate.

True, most of what I write is typed out in my house. Not just my blog, but my Jack Kirby Collector columns and my book and whatever else I'm working on. But the writing process? Where I come up with ideas and how to convey them? That goes on in my head.

People who watched Jack Kirby draw have not infrequently said that it looked like he was simply tracing some existing lines that no one else could see. Like he knew exactly what the finished page should look like, and his drawing was just a way of telling somebody else. I feel like I do that with my writing. I have been known to compose pages of text at a time without sitting down in front of a keyboard. I write and re-write and edit in my head, so that when I do get in front of a computer, I'm able to just start typing and let the already-chosen words flow out of me. Not that I do this all the time, but it's not uncommon for me.

I do this with some of my designs as well. I can picture what a page should look like, and I don't wind up doing much in the way of actual sketching because I've already composed a lot of ideas mentally. The actual mechanics of coding a webpage or putting some elements together in Photoshop rarely produces any surprises for me because I already know what the results will look like. (That said, though, I'm always keen to take advantage of those "happy accidents" when they do occur.)

I don't know if that's necessarily the same notion as creative visualization, where a person imagines themselves achieving something in order to help achieve it, but I wouldn't say it's unrelated either. I liken it more to a spatial visualization ability. But in addition to moving shapes around in my head, I can manipulate words and phrases.

Beyond that, though, that's where the words and images you see and hear get processed. Scott McCloud talked extensively about the gutters on comic pages in Understanding Comics and how that's where your brain connects disparate images into a story. And that's precisely why comics can be so visceral an experience -- you put together the story and experience it in your own mind. Your synapses are firing in much the same way as if you were experiencing it in person.

Regardless of how good an illustration is or how eloquent some wording is, where things really connect is upstairs. All these great thoughts and ideas and experiences; it's when they come from inside that they're most potent. From your own brain. Your own mind. That is where the magic happens.

I might have to bow out from actual blogging for the next day or two. Apparently, my basement flooded.

I left town last week Tuesday for a Thanksgiving vacation. I had quite an enjoyable time. I got back in on Monday, and had to quickly get back into work and making sure that I still had groceries and whatnot. I only now just went into the basement to get some laundry done, since I don't have any clean socks left. But as I stepped on one of the rugs, it went squish. Soaking wet. As was the rug next to it. And the two on the other side of the basement. And my action figure city was still sitting in a about a millimeter of water. Which doesn't sound like much, but any piece of cardboard sitting on the ground is ruined. The plastic bits seem okay, but there's at least three or four playsets that are ruined. (Including my homemade Four Freedoms Plaza!) What's worse is that the 7' x 7' homemade Tatooine playset is completely destroyed. As is the life-size cardboard R2-D2 watching over things.

I have no idea when this happened -- must have been sometime while I was gone. The pipes all seem okay, so I'm guessing we had a huge rainstorm. Maybe my sump pump died; I'll have to check on that.

In any event, I'm going to spend a lot of my free time the next few days cleaning up the basement. Blogging will resume once I get things under control.

On the plus side, all of my comics were up off the ground and weren't damaged at all.

As you may or may not be aware, last month there was a challenge going around for every creator willing to take it up to come up with 30 new characters in 30 days. I didn't follow it very closely, to be honest, so I'm not exactly sure what the purpose was -- I suppose mostly to exercise one's creative muscles. Kind of a variation on 24-Hour-Comic-Day. But my Twitter stream had more than a few updates from comic creators who joined in, and busted out a number of characters. (As I said, I wasn't really paying attention, so I don't know how many were actually successful in getting to 30 characters.)

As you may or may not be aware, last month there was a challenge going around for every creator willing to take it up to come up with 30 new characters in 30 days. I didn't follow it very closely, to be honest, so I'm not exactly sure what the purpose was -- I suppose mostly to exercise one's creative muscles. Kind of a variation on 24-Hour-Comic-Day. But my Twitter stream had more than a few updates from comic creators who joined in, and busted out a number of characters. (As I said, I wasn't really paying attention, so I don't know how many were actually successful in getting to 30 characters.)

So, now we're in December and the challenge is done. And what's going to happen to all those characters that have been created? By and large, probably nothing. Most of these folks have bills to pay and whatnot, so they're largely using their time for paying gigs and I for one am not about to begrudge them for that!

But Mark Waid pointed out that Vito Delsante is doing something a little different with his 30 new characters: he's giving them away. Here is what he actually said...Beginning today, YOU, the comic reading/comic creating public, can create comics or other similar works (film, prose, etc.) using the characters I created for the 30 Characters/30 Days Challenge. Using the Creative Commons license you see below and on the character designs, you can write, draw, compose a comic book, whatever, using one of…or more than one…of these characters.

(Emphasis his. Also a quick side note to point out that Mr. Sunday up there is one of Delsante's creations.)

He elaborated by citing Waid's keynote from the Harvey Awards -- specifically his line about “culture is more important than copyright” hitting a soft spot -- and also noted that, frankly, he won't have a chance to work on the characters himself any time soon, which would be a disservice to the characters. He does recognize that it's "probably not a great moment in comics" but still thinks it's of some significance. As does Waid, who quickly weighed in with a very positive approval and endorsement of the idea.

So the question is: what does this actually mean?

Well, from a short-term perspective, not much. After all, there ARE quite a lot of characters out there already and they're in production and have stories already in the works about them. So I don't think we're going to see Spider-Man battling Tuo, the Alligator Man any time soon. Also, there are public domain comic characters that have been available for some time and, in fact, have been used. The Golden Age Daredevil showed up in Savage Dragon last year, I think, and Dynamite Entertainment is still running Project Superpowers. Delsante's new characters aren't, in and of themselves, likely to start showing up all over the place. After all, they're new characters and have no nostalgia attached to them.

From a long-term perspective, it's hard to say what the impact will be. If the idea catches on, and creators start regularly releasing their characters with Creative Commons licenses, then we could see a cultural shift in how comics operate. Creators working for larger publishers could well start bringing in some of these "open" characters rather than create ones for themselves that would then be owned by the publisher. Of course, that's assuming the publishers would allow that type of thing! I know I've read about instances in the music industry where public domain/Creative Commons material was actively rejected precisely because it could not be owned by the corporation putting out the other material it accompanied. Similarly I can easily see editorial decisions at Marvel and DC dictating that creators cannot use Delsante's characters because, even though they don't need to pay to use them, they can't own them either. Despite still being able to earn profits from them.

See, the issue at hand really boils down to control. The executives in board rooms really don't give a rat's patootie about Alicia Masters or Perry White. They just know that they can charge a toy company X amount of money for the license to make an action figure based on that character. Because they own (i.e. control) those characters. But if the character is in the public domain, they really don't have control over him/her. Sure, they can put the character in their books and do whatever they like there, but they can't control whether or not somebody else does something different with the same character.

Remember when Jack Kirby worked on Jimmy Olsen? DC had Al Plastino and Murphy Anderson go through all of Kirby's artwork and redraw Superman's heads so that it matched the DC house style. That was about control. They wanted to ensure that Superman looked like THEIR version of Superman, not Kirby's.

Of course, Marvel and DC aren't the end-all-be-all of comics by themselves. So it's entirely possible that some smaller publishers or even independent webcomics might pick up some characters and run with them. But to what end? I'm not trying to sound pessimistic or cynical here; I really don't know. Why would they use those characters? What would that accomplish that hiring a new creator who could create (and own) his own characters wouldn't? The best I can think of is that it might provide some background fodder characters? I'm open to hearing other thoughts.

Don't get me wrong here. I like what Waid said at the Harveys and I have a lot of respect for Delsante for releasing his characters to the world. Maybe it's because it's late, but I'm having trouble seeing the real significance here. I think it's something that can and should be discussed -- which is why I'm bringing it up -- but I'm genuinely just not sure what can be said beyond the basic facts. If you've got some thoughts, please feel free to weigh in.